On February 19, the day Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) members held an internal vote in order to express their views about the party’s coalition with the Christian Democrats (CDU), the findings of an opinion poll were published. According to these very worrying findings, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party is now second in German voter preference.

This finding probably had a certain influence in SPD’s internal vote, since two-thirds of the Social Democrats voted in favour of the coalition with CDU. But what is more important is that it provoked a discussion inside the party of Angela Merkel. The question now is whether the party should abandon its position in the centre of the German political scene and move towards more conservative and rightist politics.

The ‘flirt’ of traditional centre-right parties in Europe – Christian democrats or liberals – with ideas coming from the conservative and even from the far-right arsenal is not rare or new.

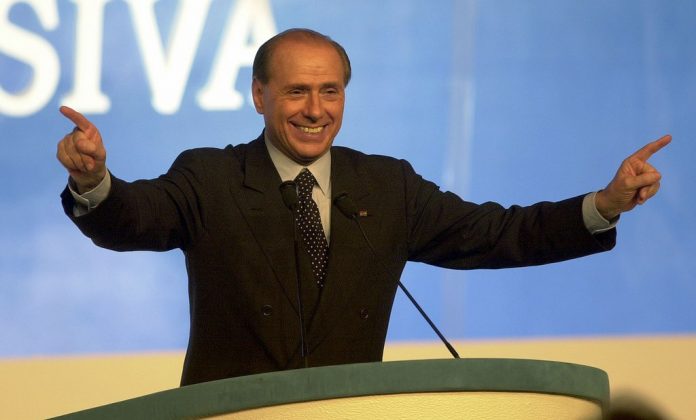

In Italy, during Silvio Berlusconi’s governments in the 1990s, the far-right parties Northern League and National Alliance were its key partners. In the Netherlands at the beginning of the 21st century, the government enjoyed the support of a far-right party. But during the past couple of years we have witnessed a generalisation of such movements from the centre-right to radical right rhetoric by some leaders of political parties in Europe.

They aimed against the easier target, namely migrants, refugees, Muslims, Roma communities, and in some cases against Jews (Hungary) and other minorities. Islamophobia, xenophobia and even anti-Semitism became their favourite narrative.

The cases of the Netherlands, Denmark, Austria, Italy, Sweden, Hungary, Slovakia, Bulgaria and Poland, is indicative of this tendency.

Mark Rutte, the liberal conservative prime minister of Netherlands, who is facing an electoral threat from the far-right Party for Freedom (Pvv) of Geert Wilders, has adapted his rhetoric to the one of his adversary. He has warned immigrants: “Act normal or go away.”

Analysing what he said during his electoral campaign, his warning could mean: “Absorb the Dutch culture or go away.”

His turn came just in time. Pvv didn’t reach the expected results.

In Denmark, the three party coalition government (two liberal parties and a Christian democrat) of Lars Løkke Rasmussen exists thanks to the extra government support of the far-right Danish People’s Party (DF). This means the government is obliged to follow a difficult chess game concerning immigration. Due to the rise of DF, Denmark’s immigration legislation, as well as its behaviour of state institutions towards refugees, has turned rather hostile.

In Sweden, the liberal conservative Moderate Party, in opposition to the coalition government of Socialists and Greens, is constantly flirting with the far-right Sweden Democrats on local issues. The result of this courtship is the considerable cuts in spending on social welfare and education programmes for migrants.

In Germany, the rise of far-right movements as the anti-Islamic PEGIDA and the Alternative for Germany (AfD) mesmerised the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) to refresh his agenda and demand – before the elections – the repatriation of the refugees.

Leading members of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) questioned whether the party should move towards the right, while the conservative Bavarian CSU has repeatedly shown positive feelings to the Hungarian Viktor Orban.

What is clear is that in Germany many conservative politicians have realised their political future is identified with a tougher or even far-right rhetoric.

In a similar vein, the coalition government in Austria between Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) and the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ) led by Heinz-Christian Strache, did not come as a surprise. This is because since 2015 Sebastian Kurz, then minister of foreign affairs and now chancellor and leader of the party, adopted most of FPÖ’s rhetoric concerning migrants, refugees and Muslims. In addition, he expressed his solidarity to Visegrad Four (Hungary, Slovakia, Czech Republic and Poland) resistance to EU’s migration policy. Kunz’s policy really doesn’t differ much of that of the FPÖ’s proposals: tougher external border controls and speed up deportations.

Italy was the first EU member state to experience the rise of a businessman, without the support of a historical political party, into government. Berlusconi’s government experience was unique for Italy as well for Europe. What is more, he included in his government two far-right parties: the separatist and, to some extent, racist (against the Italian South) Northern League. and the heirs of Italian neofascist MSI National Alliance. It was the first case of a large scale participation of far-right parties in a European government.

In the last election, Berlusconi’s electoral alliance included the inheritor of National Alliance, the party of Brothers of Italy and the openly anti-EU, anti-Euro and anti-immigration League. (as its leader Matteo Salvini renamed his party).

In Hungary and Slovakia, it is difficult to talk about a real turn to the right since the government parties of the two countries follow a policy that violates civic rights and supports an open discrimination against minorities and political adversaries.

In Hungary, Prime Minister Victor Orban has tried to justify the turn of his Fidesz party politics, since 2010, toward an ultraconservative and anti-democratic rhetoric because of the threat the rise of the far-right Jobbik party represents. But, since then Orban has moved further to the far-right. He has attacked media freedom and the right of NGOs to assist refugees and migrants, as well as the freedom of education. He also adopted a tough policy against the refugees and migrants and uses a rather racist rhetoric against Muslims and Jews.

In Slovakia, the fact that the party of the current prime minister, Robert Fico, SMER, is a member of the European Socialist family doesn’t mean that Slovak politics are free of discrimination, anti-Muslim and anti-immigration rhetoric and of attempts against media freedom. The murder of the investigative journalist Jan Kuciak and his girlfriend in Bratislava is indicative of how free the press really is.

Following the Slovak parliamentary election in 2016, Fico, formed his government, the Third Fico Cabinet, in coalition with the far-right Slovak National Party, which used a racist rhetoric against Hungarian minority and Roma population. The party often expressed his admiration for the fascist leader Jozef Tiso, the leader of the satellite Nazi state Slovak Republic (1939-1945), who was executed in 1947 for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

In both Hungary and Slovakia there is open discrimination against Roma population which affects their education, healthcare and even free movement (in Slovakia there are ‘walls’ that separate the ‘white’ Slovaks from the Roma).

In Bulgaria, the far-right is a key partner of the current government of Boyko Borisov. His right-wing GERB party, an ally of the EPP, felt more comfortable with the United Patriots, a coalition that includes IMRO, a far-right party with an open racist rhetoric against minorities, Roma population and Muslims, than with the rest of the parties of the democratic spectrum. Indeed, the far-right has two deputy Prime Ministers (the one in charge of economy and demographic policies and the second -he also holds the Ministry of Defence – in charge of public order and national security). Another four persons nominated by the far-right hold minister positions as well.

Poland, since the conservative party PiS is in government, is in an “arm wrestling” match with EU on various topics: the government’s intervention in judiciary and the media, his refusal to accept the refugee quotas decided by EU up to the fate of the primeval forest Bialowieza.

What is interesting in our discussion is Warsaw’s behaviour concerning the refugee quotas. Together with the other Visegrad Four countries (Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary) orchestrated a tough opposition to Brussels defending the right of every national government to decide for its own interest. The European Commission’s reaction was explicit! On the name of Solidarity every EU member state should participate to the quotas programme.

But, in December 2017 a thunderbolt menaced the cohesion of Brussels’ front.

Donald Tusk, European Council President, qualified mandatory refugee quotas as “ineffective” and “highly divisive”. This was part of a document which included some thoughts of the former Polish Prime Minister concerning EU asylum policy which were very close to those of the Visegrad Four position.

Despite the angry reaction of many Commissioners and state leaders, Tusk, after meeting the new Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kunz, declared that he has similar views with him concerning migration and that it would be necessary to find a common European policy that will avoid future divisions in Europe.

Rumours in Warsaw may explain Tusk’s move towards the positions of PiS concerning migration. According to these rumours, he wants to return to the political scene of Poland, probably as a presidential candidate.

The self-preservation instinct of the politician worked once more? Polish presidential elections are scheduled for 2020.

As a conclusion, Christian democratic and liberal parties in Europe understand that austerity policy applied in EU member states since 2010 created a Europhobic environment. This was aggravated by the refugee crisis and the mass migration influx. The ‘ghost’ of an omnipotent ‘Islamic fundamentalism’ added to the factor of fear to the sentiments of the already angry European citizens.

In such an environment, far-right parties know how to create political profits. The parties of the centre-right as well as the Social-democrats, failed to do so. There were two ways to react. One was to be adamant in their fundamental principles of democratic values and respect of the pluralism that characterises European societies. The second was to follow the stream and to adapt properly their policies. Their instinct of survival told them to follow the second way that was the easier.

In doing so, they are helping to create a society that moves away from the fundamental principles of the European Union. And this is not only worrying, but very dangerous.