On Monday, 5 February, the European Parliament debated the conditions of the Hungarian prisons. It is not the first time Hungary is at the centre of international interest because of the way it treats prisoners.

According to Eurostat, in 2021, Hungary (and Poland) had the highest prisoner rates per 100,000 people in the EU. However, prison overcrowding is one of many problems with the prisons in the country.

In its 4 February report, the Hungarian Helsinki Committee (HHC), a human rights NGO, notes the disregard for Human Rights, the disproportionate use of physical restraints, and the overall inhumane conditions in the prisons.

This situation, as HHC points out, affects quite 40 thousand detainees every year and impacts the 100 thousand members of their families.

European Interest had the opportunity to interview Lili Krámer, a Sociologist-Criminologist, project manager, and policy researcher at the Justice Programme of the HHC. Ms. Krámer regularly contributes to HHC’s reports to the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers on detention conditions under the ongoing procedure, within which the European Court of Human Rights established that prison overcrowding and substandard detention conditions constitute a structural problem in Hungary. She has managed projects at HHC promoting non-custodial sanctions to prevent prison overcrowding, making criminal procedure more accessible. Additionally, she is one of the founding members of a grass-roots community support network for people impacted by incarceration, FECSKE.

European Interest: Why is Hungary’s number of persons held in pre-trial detention or prison rising?

Lili Krámer: The reasons are complex: the sharp increase in the number of persons detained in Hungary resulted in an unprecedentedly large prison population; prisons in the country hold around 19 thousand people nowadays. One reason is the decision makers’ lack of focus on tackling structural problems related to the criminal justice system. A related issue is the government penalising other areas of life that go hand in hand with the severe cuts on social spending, which leads to all sorts of problems, such as the criminalisation of poverty. An example is “school avoidance”, constituting a petty offence in the Hungarian system. If a child under 16 misses 30 classes in a school year without justification, their parents must pay a fine. The fines are almost exclusively imposed on the most deprived, mostly Roma parents, whose children often travel a lot to their school that are difficult to reach by public transport. Here is a video with English subtitles explaining this phenomenon more.

Further factors leading to a growing prison population identified by the Hungarian Helsinki Committee are the following:

- Non-custodial alternatives to imprisonment – such as community service or electronic monitoring – are underused in all phases of the criminal procedure in Hungary (during the trial phase, at sentencing and at the penitentiary judge’s decision-making regarding whether to apply an early release measure).

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Hungarian criminal justice system resorted to custodial solutions while not taking any steps towards reducing the frequency of entries into prisons or increasing the rate of release from prisons, not even in the case of vulnerable (such as juveniles, the elderly, people with health risks), low-risk offenders, including non-violent offenders who only had a short amount of time left of their sentence were any steps taken toward their extraordinary early release with electronic monitoring as in other European countries.

- Pre-trial detention is the most commonly used coercive measure, even though other, less severe measures are available in the Hungarian criminal procedural system. In Hungary, on the last day of 2022, while 2561 people were held in pre-trial detention, only 764 people were under house arrest with electronic monitoring.

The big difference between other EU countries and Hungary is that other countries allow civil society into prisons to monitor conditions and support reintegration programmes; what is more, they rely explicitly on civil society to help them. Reintegration cannot be achieved in a prison system hermetically sealed off from the world. Since civil society cannot access Hungarian prisons, I have visited more prisons abroad in the last few years than in my home country. For example, I visited a women’s prison during a professional conference last year in Portugal. This facility was more like a dormitory or a school rather than a historically interesting but outdated 200-year-old prison that we have a few of in Hungary.

In that facility in Portugal, it was not just the good physical conditions that fascinated me but also the way of thinking. Members of the prison management were exhibiting a different attitude towards their task than what we are used to in Hungary. Hungarian prison management frequently points out prisons are not luxury spa resorts or Michelin-starred restaurants. In contrast, their Portuguese counterparts spoke about how hard they are trying to run humane prisons that fully respect detainees’ human rights and dignity. Not because the Portuguese have such a beautiful soul or because they are rich – the size of the country’s population and economy is very similar to that of Hungary – but because they have long recognised that this is what works. If we don’t take someone who has committed a crime away from their family, they will have somewhere to go home to, something to rely on to start again. Preserving family bonds is an essential element of reducing the chances of reoffending. These prison systems realise that family members are not their enemies but their allies. It is, therefore, in the penitentiary system’s interest to support the restoration and strengthening of family ties. In this Portuguese prison, there was no Plexiglas partitioning in the visiting room. Moreover, I have been in several Spanish prisons and have never seen partitioned visiting rooms. In other prison systems, the prohibition of physical contact with visitors is a rare exception; it is only ever used when there is a reasonable fear that someone might smuggle in a prohibited item.

European Interest: The situation in Hungarian prisons is depicted as deplorable, including the quality and quantity of food and poor hygiene. Is this because the authorities want to punish farther the people convicted or because the system of detention has collapsed?

Lili Krámer: At the heart of these issues is a lack of political will to engage with a restorative, non-custodial, criminal policy where imprisonment is only utilised as a last resort. This non-engagement of decision-makers leads to insufficient inter-agency cooperation and an austerity-ridden, underfunded social protection system, contributing to structural problems resulting in substandard material conditions. The under-utilisation of alternative sanctions contributes to prison overcrowding, which leads to an overburdened prison administration suffering from severe permanent staff shortages. Furthermore, austerity regulations severely erode the country’s social protection and welfare institutions and directly affect material detention conditions (such as access to heating, proper food and healthcare).

European Interest: According to reports, prisoners appear in Court in shackles and handcuffs, in violation of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) standards. Nine years ago, ECHR condemned Hungary for inhuman treatment of detainees. However, the situation seems unchanged. Is this an ideological approach of the government?

Lili Krámer: When using coercive measures before the Court, such as shackles and handcuffs, we see a general tendency that is typical of the Hungarian authorities. Authorities are extremely security-centred and are not willing to change their policies just for the sake of bringing human rights principles into practice. Another similar example is that in prisons, during visits, detainees are prohibited from any physical contact with their visitors; a plastic wall separates them. The Prison Administration introduced this policy seven years ago; those affected had no choice but to tolerate these circumstances during visitation, which is a large-scale violation of their fundamental right to respect private and family life. The Hungarian Helsinki Committee (HHC) has been striving to end this practice since 2017. Recently, in October 2023, based on the application of the family members of a detained man serving his prison sentence in Hungary, the European Court of Human Rights established that the State cannot employ an overall ban on physical contact between detainees and their family members during visits. In the Takó and Visztné v. Hungary case, the Court upheld the Hungarian Helsinki Committee’s argument: security considerations cannot be regarded necessary without individual risk assessment, and the State does not have a free hand in introducing restrictions in a general manner without determining whether the limitations are appropriate in specific cases. In the past fourteen years, the government did not consider such principles. But this decision gives reason to hope that sooner rather than later, decision-makers will recognise the need to balance their policies to uphold human rights standards.

European Interest: In 2016, it was reported that prisoners were forced to work in the construction of the border fences, intending to stop migrants from entering the country. Are there cases of forced labour of prisoners in Hungary?

Lili Krámer: The HHC has not received information alleging forced labour in Hungarian prisons. As in many European jurisdictions, it is mandatory to work inside local prisons with a few exceptions (for example, mothers with children or those with a health condition). However, detainees cannot be forced to work outside the prison walls unless they consent to, for example, doing construction work at the border. The HHC often receives complaints from detainees about bad working conditions, especially when they are working outside the prison facilities.

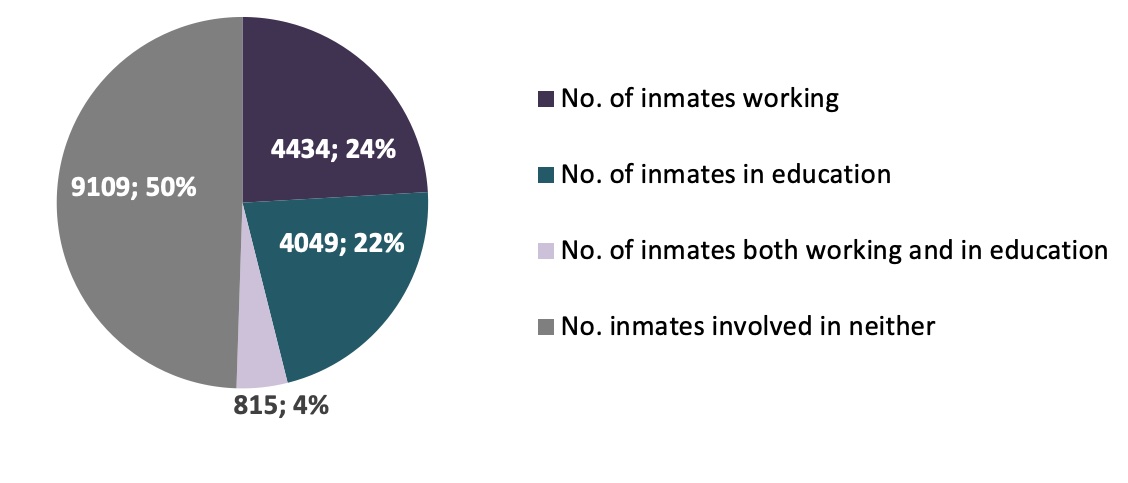

However, most of the time, the problem is that there is nothing to do within these institutions because there is not enough work available. Data show that on 31 October 2023, only 24% of incarcerated people were working inside Hungarian prisons. Detainees often report that working is better than sitting around all day locked in a cell.

Number of inmates working, in education, both and neither on 31/10/2023

The chart above shows that prisoner reintegration and educational activities operate at low intensity in Hungarian prisons. On 31 October 2023, half of incarcerated people in Hungary were not involved in either working or education.

European Interest: What is the number of Roma imprisoned? Are among the detainees people convicted for “crimes” related to homelessness? Do the authorities treat these categories in more severe ways?

Lili Krámer: Most EU Member States do not collect criminal justice statistical data disaggregated by ethnicity either because law prohibits it or it is not standard practice. The former is true in Hungary’s case: national law prohibits data processing on ethnicity at any stage of the criminal procedure. Therefore, it is challenging to measure ethnic disparities within the criminal justice system. However, research shows that discriminatory attitudes infiltrate many European countries’ criminal justice systems, including Hungary as well. Roma communities have been smitten by systemic socioeconomic marginalisation for decades in Hungary, which resulted in widespread discrimination, exclusion, unemployment, housing and educational segregation, all resulting in large-scale extreme poverty. There are no programmes for criminal justice professionals on anti-discrimination. Additionally, the government has only ever engaged in creating exclusive and punitive criminal policy; people of Roma origin are certainly more prone to being subjected to petty offences and criminal procedures than non-Roma.