EXARCHEIA, Athens – On a summer day in Athens, tourists and locals alike can be found in Kolonaki, one of Athens’ most affluent neighborhoods, sipping on cappuccinos, chatting with friends, or leisurely walking alongside the most expensive stores in the city. Few ever leave to go to Exarcheia, a neighborhood that is a mere five-minute walk away.

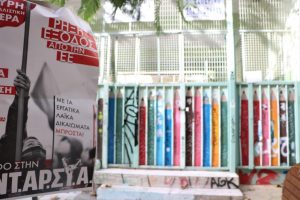

Although Kolonaki and Exarcheia border each other, they are worlds apart. Kolonaki offers clean alleyways and expensive coffee shops, and houses Athens’ only Gucci store. In Exarcheia, graffiti cover buildings, streets and any other available surface. Posters on lampposts urge passers-by not to vote in the next elections. Squatters have a smoke in front of their illegally occupied homes.

Anarchists have turned many of the buildings in Exarcheia into squats. Some of them house refugees. (Photo: Anna Wolcke)

For the last four decades, Exarcheia has been controlled by anarchists. Travel agencies warn tourists of entering the neighborhood. And the police refrain from getting too close.

At the same time, Exarcheia is a hub for young people interested in street art, alternative bars and counter-culture vibes. Anarchists explore Communist bookshops, enjoy a cold beer at anarchist-run rooftop bars and discuss politics in the streets.

But in a few months, Exarcheia as it stands might not exist.

The fate of the anarchists who call the neighborhood their home? Unknown.

New Democracy’s Plans to Clean Up Exarcheia

New Democracy, the center-right political party that won the Greek legislative elections in July, has declared war on the anarchists and Exarcheia.

New Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis has long been critical of the anarchists and their presence in Exarcheia, promising to restore “law and order” to the neighborhood that he says is ruled by lawlessness.

“I will clean Exarcheia,” Mitsotakis said in a 2017 speech.

“If they give us a mandate, we will not only clean them up, nor will a mosquito stay in Exarchia,” said Stavros Balaskas of the Union of Police Officers in an interview with a Greek TV channel shortly after the elections.

Asked about what fate exactly will await the anarchists, a spokesperson for New Democracy declined to comment, instead referring to Mitsotakis’ speeches.

“The Worst Kind”

Athenians have been increasingly frustrated with the anarchist movement in Exarcheia.

“I’m not sure who exactly the anarchists are anymore and whether they are pure in their intentions,” said Liana Theodoratou, who grew up in Exarcheia and now serves as the director for New York University’s summer program in Athens.

“They are the worst kind,” said Viktoria Karatza, who studies architecture at National Technical University of Athens, in Exarcheia. “Many times they start ‘fights’ with the cops in the area. They come inside the university, break the marbles [paving stones] and throw them to the cops. They destroy our buildings.”

The architecture compounds of Polytech Athens University in Exarcheia are covered in graffiti, disturbing some of its students. During a recent afternoon visit, a young man holding a stick in his hands was yelling at two adolescents sitting in the courtyard. (Photo: Anna Wolcke)

Some anarchists themselves are frustrated with the movement.

“I’m just really disappointed in the movement as a whole,” said 22-year old psychology student Antonis, who identifies himself as an anarcho-communist with no affiliation with a specific anarchist group.

“There’s no direction” in the movement, he thinks. Antonis did not want to share his last name, afraid that “the wrong people” will be after him if they found out that he had talked to a journalist.

“A lot of people think it’s treason to talk to journalists,” explained Jason, who said he was part of two influential anarchist groups for more than a decade. He, too, asked for his last name to remain anonymous.

Who Are The Anarchists?

But it is precisely due to the anarchists’ secrecy that local Athenians feel alienated from the movement. Outsiders are rarely allowed a glimpse inside the loosely organized network that makes up the movement.

Othon Alexandrakis, an anthropologist who wrote an ethnography about anarchists, explained that getting to know anarchists in Athens involved a long process of introducing and proving himself. You have to “wait until they discuss you and decide whether you’re worthy of staying,” Alexandrakis said. He spoke with higher-level anarchists only after being in the anarchist scene for five years.

So who are the anarchists?

Interviews and research suggest that some anarchists are part of terrorist groups, but most are not. Some spray graffiti on public buildings, some throw Molotov cocktails at the police, some march the streets wearing masks and holding baseball bats, and some do not. Some house refugees in illegal squats. Some steal and burn ballot boxes – others do not.

“It’s dangerous to lump them all together,” said Jason.

In general, an anarchist is “somebody who does not want to be governed by a constitutionally determined political system,” explained Sophia Papaioannou, professor of Latin literature at the University of Athens. “They don’t want to be told what to do, they don’t want to pay taxes, they don’t want to be controlled and all that.”

As a professor in the School of Philosophy, Papaioannou has first-hand experience of an anarchist attack. Since November, an administrative office of the university has been taken over by the anarchist group Rubicon (Rouvikonas in Greek) and turned into a small anarchist headquarter in which the group hosts so-called “office hours” for students. Professors who tried to enter the office were violently kicked out.

The goal of the anarchist movement: “To make it increasingly more challenging for the state to advance their agendas,” said former Exarcheia resident Theodoratou. To “create a society that revolves around the human needs and environment needs and animal needs and social needs instead of capitalism,” said anarcho-communist Antonis.

Escalating Violence

The Athenian anarchist movement of today first gained strength in 1973, when it joined the anti-dictatorship student protests at the National Technical University of Athens in Exarcheia, or Polytech Athens, as it is more widely known. 40 protesters died on university grounds after the military entered with a tank.

Following the fall of the dictatorship, the Greek Parliament passed Law 1268/82, better known as the University Asylum Law. The law bans police from entering universities except for vaguely defined life-threatening situations. Ever since, Polytech Athens – at the heart of Exarcheia and of the protests – became a refuge for the dissident.

And Exarcheia became home to many anarchists.

At first, many locals appreciated the change that the anarchists brought about in Exarcheia. “They’ve shaped and maintained the anti-authority character and feel of the neighborhood over the years, which in turn has attracted a lot of artists, socially-forward organizations of various kinds and others who regard the area as ‘cool’,” said anthropologist Alexandrakis.

In fact, the anarchist movement was quite popular. After the dictatorship, the movement managed to raise “issues which the traditional left parties were more or less ignoring,” said former anarchist Jason. Among them: “Queer politics, active solidarity to immigrants, protest against police violence, street anti-fascism, etc.”

But what started out as a counter-cultural movement soon became more radicalized in 2008, after the death of 15-year old Alexis Grigoropoulos – who was shot and killed by police in Exarcheia – led to riots that unsettled Athens for weeks.

Graffiti and information boards in Exarcheia remind of 15-year old Alexis Grigoropoulos who was shot and killed by police. (Photo: Anna Wolcke)

The 2008 riots were a turning point after which anarchists realized their political power and “started forming violent groups,” as former anarchist Jason explained. The riots, together with the outrage caused by the financial crisis two years later, led to what he calls as a “cult of violence” among the anarchist community.

“Outlaw mentality became part of their DNA,” said professor Papaioannou.

What followed was a string of terrorist attacks committed by anarchists.

Within the last year alone, there have been multiple attacks. In December 2018, a bombing by anarchists at an Orthodox Church in Athens left two people injured. In March, anarchists assumed responsibility for a grenade attack at the Russian consulate. In May, the anarchist group Rubicon threw red paint and set off two smoke bombs at the Parliament in support of the incarcerated terrorist Dimitris Koufontinas.

While few attacks lead to serious injuries, “you cannot in any way separate anarchists from violence anymore,” said former anarchist Jason. Anarchists were part of a 2011 riot in which protesters attacked a bank with petrol bombs. The attack killed three people, among them a pregnant woman.

No one was ever charged with the deaths. But Jason said he wished that the anarchist community had stopped and reflected on what happened that day. There was an “irresponsibility toward the result of the violence that was escalating and escalating” Jason said.

Ultimately, Jason could not take it anymore. He left the movement in 2011.

“I think it was an accident,” said Victor, who is a leading member of Rubicon, about the deaths. Rubicon – currently the biggest anarchist group with 80-100 members, formed in 2013 – is known for vandalism, raids and invading the Defence Ministry. Victor refused to share his last name, asking, “do you want me to go to prison?”

VOX, headquarters of the anarchist group Rubicon. The building overlooks the main square in Exarcheia. (Photo: Anna Wolcke)

Victor defended Rubicon’s use of violence, contending that the Greek government is violent by not providing well for its citizens. “If you don’t have enough to eat, that is violence (…), not the rocks or Molotovs.”

“We don’t like illegal things, this is not the point, we don’t like murder, we don’t like rape, we’re against that, period. But when a system becomes oppressive, I believe there’s no problem with doing illegal action,” said Antonis.

Ultimately, Victor believes that anarchy is “an ideology of love, not violence.” But “violence is a necessary evil.”

Jason emphasized that, while violence became a framework of discussions among anarchist groups, the extent to which members were willing to use violence varied.

And most anarchists are not part of a terrorist group. “I’m an anarchist but I’ve never thrown a Molotov cocktail,” stressed Antonis.

Nevertheless, many locals avoid Exarcheia. Today, the neighborhood is under full control of anarchists. Police enter the neighborhood only for emergency situations.

And when they do, they wear full riot gear.

Anti-What, Exactly?

The violent attacks have turned many locals against the anarchist movement.

In an open letter, Exarcheia residents complained that lawlessness was ruling their neighborhood, with perpetrators invading homes, burning cars, and vandalizing public property.

“They believe that we’re just thugs,” Antonis said about the relationship between locals and anarchists.

“I don’t know what is the main goal, I really don’t know actually,” said Marques about the movement. Marques, a native Portuguese, has lived in Athens for more than three years. “Most of the times I feel that it’s just empty gestures.”

“They use language that is very politically loaded, but they don’t have really anything to say,” said Papaioannou, who has had many discussions with students who identify as anarchists. “If you are an anarchist, you react against something else, you don’t act to achieve something for the members of your party.”

Exarcheia Square is one of many sore spots in recent anarchist history.

Since anarchists drove out the police from Exarcheia, the neighborhood’s main square has become a popular spot for drug dealing by members of the Albanian mafia. Because the police do not go near the square anymore, anarchists seem to have taken on the role of law enforcement, violently driving out drug dealers.

“I don’t think Exarcheia is the place to have free drug dealers,” said Rubicon-member Victor. Rubicon has an illegal squat named VOX by the main square that has been under the group’s control since 2012.

Recent incidents have further sparked public outcry among Athenian locals. Below, an in-depth look at three of them.

— Weekly Riots and Vandalism —

In the last two months alone, anarchist groups have made headlines multiple times. On the Thursday before elections, Rubicon attacked the offices of the media company Athens Voice for publishing a comment about the death of a nurse that the group deemed sexist and racist. The same group staged a protest at the hospital at which the nurse had worked before her death.

A week before the raid on the media company, anarchists attacked riot police with Molotov cocktails in Exarcheia.

In fact, clashes with the police have become an almost weekly occurrence in Exarcheia. While Antonis condones some types of violent action – he fights supporters of Golden Dawn, Greece’s ultra-nationalist far-right party, with plastic sticks at rallies – he criticized the weekly clashes.

(Photo: Courtesy of Antonis)

“There’s no point, we are feeding the spectacle,” he said, explaining that the clashes only add to anti-anarchist sentiment among the locals. “It’s not effective because you break one glass, so what?”

Marques, who lives close to Exarcheia, is skeptical about the outcome of the clashes. “I throw Molotovs on Saturday, thus I’m an anarchist. But what does it make? What are the changes that it makes?”

— Misguided Solidarity —

With the refugee crisis that began in 2015, some anarchists have taken it upon themselves to house migrants in illegal squats in Exarcheia. Unlike refugee camps, the squats are meant “to create communities with the immigrants, not just store them there,” explained Antonis. “It’s illegal but it’s humane.”

Others are less optimistic about the squats. Karatza, an architecture student at Polytech Athens in Exarcheia shared her frustration with anarchists who establish the squats. “A lot of times they take over our building. One time they put in refugees in a building for classes. The refugees lived in very bad and dirty condition about four or five months and we haven’t enough classrooms for lessons.”

Marques was concerned about how anarchist protests affect the refugee community. “The smell of tear gas might trigger all of those traumas that they fled,” he said.

— Ballot Box Theft —

On July 7, shortly before balloting for the Greek legislative elections closed, Athenian Twitter users shared that a ballot box in Exarcheia had been stolen. Minutes later, the Greek newspaper Kathimerini reported that a group of hooded anarchists had burned the ballots inside the box.

According to the newspaper, the perpetrators used a sledgehammer and threw tear gas to threaten employees at the polling station.

Less than four hours later, the self-proclaimed anarchist group Ballot-Seeking Arsonists assumed responsibility for the attack with a post on the anarchist online platform Indymedia.

“This action is a warm welcome on our part to Kyriakos Mitsotakis and New Democracy, who have promised to finish with us. We are waiting for you,” the group wrote. Mitsotakis, the president of New Democracy, assumed his role as Greece’s new prime minister in July. The post by Ballot-Seeking Arsonists was accompanied with the tags “fuck the law” and “the revolution first and always.”

At this polling station in Exarcheia, anarchists stole a ballot box and burned the ballots inside during the recent legislative elections. (Photo: Anna Wolcke)

The exact purpose behind stealing and burning the votes remains unknown. Rubicon-member Victor was not part of the attack but explained that “all the things we do is a statement.”

Then-Interior Minister Antonis Roupakiotis ordered new elections to be held at the polling station in Exarcheia a week from the elections.

A Twitter user who calls himself The Greek Analyst tweeted that the ballot theft was “a profound insult to the Republic and to those citizens who voted today.”

Antonis, who identifies himself as an anarchist, simultaneously criticized and defended the ballot box theft, equating what he perceives as the pointlessness of the attack with the pointlessness of elections: “Yeah there is no point. The same way that there is no real point in the elections.”

Future for Anarchists?

With New Democracy in power, no one knows what will happen to Exarcheia and its anarchist residents.

Two weeks after the elections, Giorgos Kalaitzidis, a leading member of Rubicon, was arrested by local police. He was charged with incitement following a paint attack on the Athens headquarters of the Hellenic Federation of Enterprises in July. In early August, two other members of Rubicon received prison sentences for the attack.

A few days ago, the Greek Parliament revoked the University Asylum Law. Prime Minister Mitsotakis had promised to abolish the law during his campaign, aiming to keep out anti-establishment groups from universities.

Last Monday, the government revealed first details about its plan to remake Exarcheia. The makeover will reportedly include evicting people from squats.

“We’re not worried,” said Rubicon-member Victor, expressing confidence that anarchist groups in Athens will come together and face New Democracy. “Exarcheia is still here,” he said.

Former anarchist Jason was less optimistic. Many of the people he knew in the anarchist movement have long left, feeling alienated from the violence used by many anarchists.

Does he see a future for the movement? “Not really,” he said. In his eyes, the movement has lost all political power in Greece.

But, like Victor, he believed that any attempt by the new government to remake Exarcheia will lead to a temporary strengthening of the movement. “If anarchists know how to do something well this is definitely resisting police repression.”

An Office For Anarchists – Room 516 In The School of Philosophy In Athens

![]()

When the anarchist group Rubicon took over room 516 in the School of Philosophy, they painted the door black and decorated the wall next to it with a read Communist star. The group has been in control of the office since November. (Photo: Anna Wolcke)

From the outside, the School of Philosophy in the University of Athens looks like any other university building: Nine floors of gray walls, posters, classrooms and a small cafeteria. Students sit on benches, studying for their final exams, and professors hurry past. On a first glance, everything seems normal.

Except for room 516. A big red Communist star decorates a door painted in black. Graffiti and paint cover the floor.

What used to be an administrative office of the university has been controlled by the anarchist group Rubicon (Rouvikonas in Greek) since November.

After Rubicon first took over the office on the fifth floor, the university changed the lock. The group came back with chain saws, took over the room and barred professors from entering.

“They violently kicked out people who tried to get in, including professors,” explained Sophia Papaioannou, professor of Latin literature.

The entrance to the School of Philosophy. (Photo: Anna Wolcke)

Because of Greek University Asylum Law 1268/82, the university has been unable to seek help from the police. The law was passed after 40 people died at Polytech Athens University in 1973 while protesting the military dictatorship then in power. Ever since, the police do not enter Greek universities except for vaguely defined life-threatening situations.

As a result, Rubicon has been able to stay in room 516 without facing arrest, leaving the university powerless.

What Rubicon uses the room for is mostly unknown. Papaioannou explained that the group held office hours last semester. Students could inform on professors who they thought were Fascists. The group would then offer to “take care of the bad things happening at the school,” said Papaioannou. So far, no professor has reported a violent confrontation involving a member of Rubicon.

More than seven months later, the university seems resigned to its fate.

“Somehow you try to ignore it,” sighed Papaioannou, looking at the locked door to room 516. “We don’t see them, we don’t hear them, we pretend they’re not there.”

Over recent months, Rubicon has been making headlines in the Greek media. In August 2018 the group invaded the foreign ministry building in Athens. In February 2019 they posted a video that showed them smashing the windows of a department store. In May they raided a law office in Athens and a member of Rubicon was arrested for throwing red paint on the Parliament’s walls and setting off two smoke bombs.

“It’s become a quasi-terrorist organization,” Papaioannou said.

While the group has not taken over any other rooms in the University building, their presence is ubiquitous. The anarchist symbol with the letter A inside a circle is sprayed on many walls and floors of the university building.

A poster showed members of Rubicon wearing masks and holding Molotov cocktails. Below the image was a list of demands.

Posters like these hung in the hallways of the university building. Titled “This Is War,” the posters contained lists of demands by the anarchist group Rubicon. The symbol on the right of the posters is the symbol for anarchism. (Anna Wolcke)

Food should be free for all students at the university, read one. Papaioannou explained that the cafeteria on the first floor offers free food for the students already. Universities should be free for all students, read another. But the right to free education is embodied in the Greek constitution.

A second poster urged students not to vote in the upcoming legislative elections. “When you vote you surrender to exploitation,” it read.

Other posters near elevators and on walls throughout the building invited students to anarchist parties. One of the posters was from April. But the cleaning staff of the university is afraid to take down anarchist posters, explained Papaioannou.

So the posters stay on the walls. And room 516 remains closed.

Anna Wolcke is a German Princeton University journalism student. Anna spent five weeks on the ground in Athens under guidance of veteran Washington Post investigative reporter Joe Stephens.